CALIFORNIA: THE PERFECTED NGO MODEL

They didn’t lose control of the money. They built a system so no one else could follow it.

INVESTIGATIONS: By Walter Curt

The California leg of this investigation didn’t introduce chaos or confusion. It introduced clarity. What emerged wasn’t a story of missing paperwork or overwhelmed agencies. It was a landscape where the money moves smoothly, the explanations pile up, and the ability to see end-to-end quietly disappears. The deeper the look went, the more consistent the pattern became. California doesn’t struggle to explain where the money goes. It has arranged things so the explanation never quite arrives.

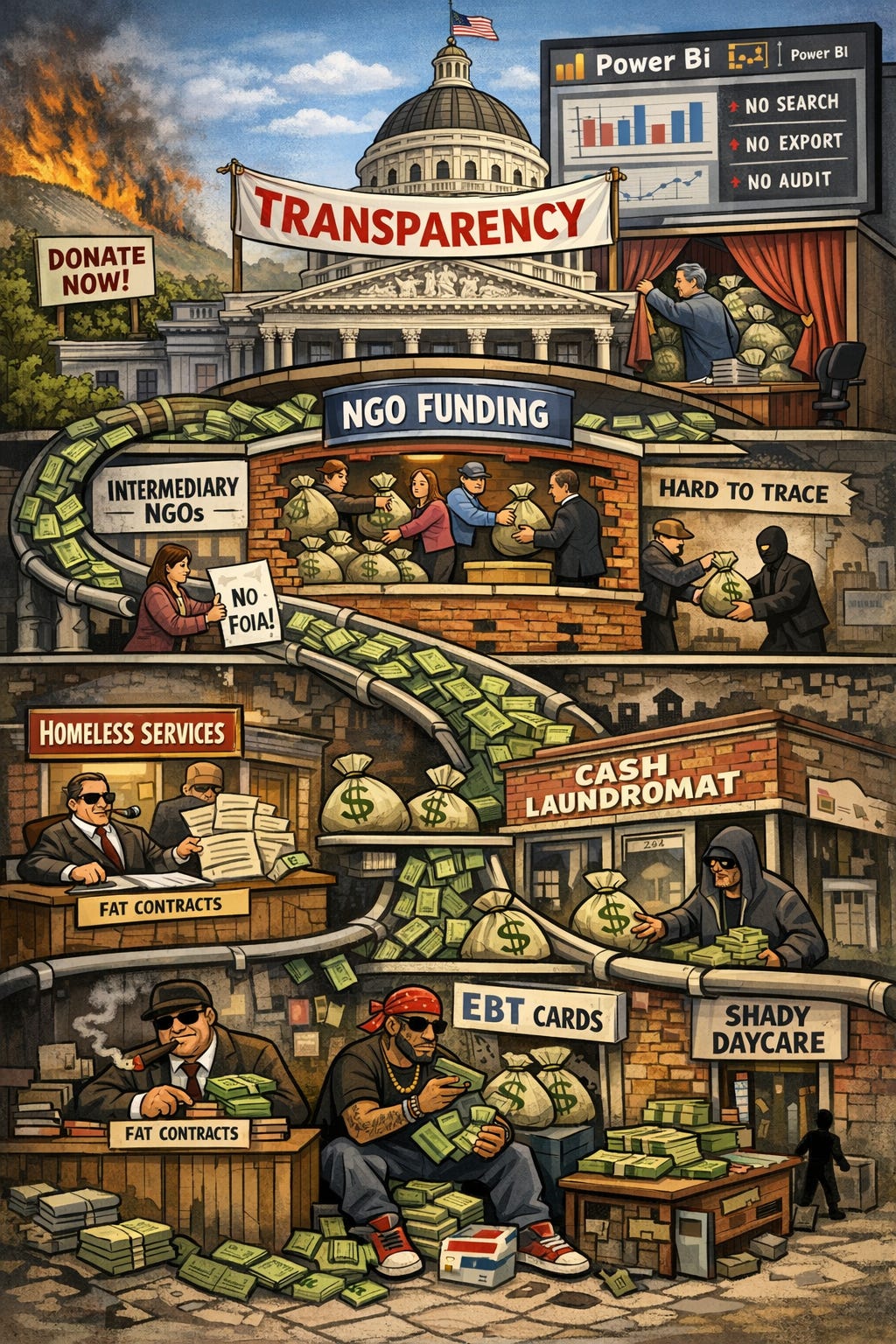

The state gestures toward openness by pointing to its procurement data, neatly housed inside a Microsoft Power BI dashboard. It looks modern. It looks official. It looks like progress. You can click around, watch numbers change, admire the graphics. What you cannot do is search meaningfully across vendors, export the data, run comparisons, or test hypotheses. You cannot pull the information into your own system and ask basic questions at scale. You are allowed to observe. You are not allowed to analyze. The difference is subtle enough to pass a press release and strong enough to stop an audit cold.

That distinction matters once the full dataset is actually laid out. When the information is pulled in its entirety and organized outside the state’s presentation layer, the scope becomes impossible to miss. More than 1,100 vendors associated with humanitarian-related contracts. Roughly $8.8 billion flowing through them. Not scattered grants. Not pilot programs. An economy of vendors, operating continuously, funded at scale. The dashboard never highlights that universe. It doesn’t need to. It only needs to make seeing it difficult enough that most people never try.

At the same time, at the federal level, the Small Business Administration acknowledged what everyone working in procurement already understands. Billions of dollars under review. Tens of thousands of entities flagged for potential fraud exposure. Large systems, large sums, limited verification, delayed audits. The numbers don’t have to match perfectly to rhyme. They already do. When separate data streams begin pointing toward the same structural vulnerabilities, the story stops being about isolated actors and starts being about architecture.

Requests for clarity meet resistance long before they reach conclusions. Public records requests stall. Narrow questions expand into bureaucratic negotiations. Specific funding totals become “unavailable.” Amy Reihart’s experience in San Diego fits neatly into this rhythm. The data is said to be public, but pulling it cleanly proves elusive. The formal channels exist, but they lead nowhere quickly. What’s left is a familiar posture from the state: the information is technically available, practically unreachable, and always just one more step away.

The same rhythm shows up in how California moves money on the ground. Childcare subsidies offer a clean example. In many states, the government pays providers directly. The path is short. Attendance aligns with eligibility. Eligibility aligns with reimbursement rates. Payments can be checked against records without heroic effort. In California, that line bends. Funds are routed through intermediary NGOs charged with administering the program. The state pays the intermediary. The intermediary interfaces with providers. Documentation flows inward. Payments flow outward.

Following that path takes work. First, identify which NGO controls which geography. Then locate its audit filings, assuming they are current and complete. Then reconcile those filings with procurement records that are already difficult to interrogate. Only after that does the provider level come into view. Each step adds distance. Each handoff adds discretion. Sources describe monthly subsidy flows exceeding $1,400 per child with minimal verification. Whether every dollar is misused is unknowable from the outside. What is visible is how easily the structure absorbs misuse without producing alarms.

That same opacity shows up beyond childcare. Walk through downtown Los Angeles and the conversations repeat. Not policy debates. Observations. Barbers, bartenders, people who work late and walk home early. The homeless system comes up unprompted. Everyone knows how much money moves through it. Everyone knows how little seems to change. Deliveries arrive at storefronts with no customers. Benefits circulate with minimal identification. Stories circulate about organized applications and quiet laundering through approved channels. None of this appears on a dashboard. It doesn’t need to. It lives in the gap between official narratives and daily experience.

The system doesn’t rely on secrecy. It relies on diffusion. Money enters labeled as humanitarian assistance, housing support, community partnership. It passes through nonprofit layers that soften scrutiny and multiply explanations. By the time it reaches the ground, responsibility is spread thin enough that no single ledger tells the whole story. Each participant can point upward or downward and remain technically correct. Oversight exists everywhere in theory and nowhere in practice.

Organizations operating at the intersection of activism and public funding sit comfortably inside this environment. The Solidarity Research Center in Los Angeles, connected to broader political networks, is one example drawing attention. Not because of slogans or mission statements, but because proximity to power and insulation from scrutiny tend to travel together. When funding, politics, and moral language overlap, questions are framed as attacks and audits become optional. The structure does the work long before anyone has to defend it.

The contrast between damage and response is hard to ignore. Drive through the Palisades fire zone and the destruction remains visible. Burned properties. Long stretches untouched. The rebuild lags. The NGO signage does not. Clean placards promise recovery, resilience, and renewal, often paired with donation links. The messaging arrives faster than the materials. The branding arrives faster than the permits. Money is already being organized, even as the outcomes remain distant. It’s a familiar sight in California: urgency in fundraising, patience in results.

None of this happens by accident. The systems are too consistent. The barriers appear in the same places. Presentation layers substitute for access. Intermediaries substitute for accountability. Requests for detail meet friction rather than answers. The result is a machine that keeps moving regardless of whether anyone outside it can explain how. For the people inside, it works. For the public, it produces impressions instead of records.

That’s what makes California instructive. The state isn’t merely dealing with a fraud problem. It demonstrates how modern institutional spending can operate at scale while remaining difficult to map. Publish data without enabling analysis. Route funds through nonprofits that fracture the audit trail. Treat information requests as burdens rather than obligations. Over time, the pattern normalizes. Oversight becomes ceremonial. Accountability becomes abstract.

The next phase of this work moves away from generalities. Specific NGOs. Specific businesses. Specific contract numbers pulled from the dataset. Procurement records cross-referenced with IRS 990 filings and SBA data. Once those threads are tied together, the picture sharpens quickly. The question stops being whether irregularities exist and shifts to how deeply the structure depends on them being hard to see.

California offers a preview of what happens when scale, technology, and moral framing converge without meaningful transparency. The money keeps flowing. The dashboards keep spinning. The answers stay just out of reach. What looks like complexity from the outside functions as stability on the inside. And that is why this model matters. It doesn’t require secrecy to survive. It only requires that seeing clearly takes more effort than most people can afford.

This is how the Democratic Party and its allies work everywhere. It's obvious now.