Caracas Is a Message to Beijing

The Cold Trade War has a Scoreboard. It’s Written in Crude, Shipping Risk, and Silver.

OPINION: By Walter Curt

They want you to believe every major geopolitical event is “complicated,” accidental, and disconnected. They want you staring at the spectacle, another headline, another “crisis,” another panel of experts saying nothing, while the real contest moves underneath. So let’s say the quiet part out loud: the United States is in a cold trade war with China, and oil is one of the main pressure tools. Maduro’s reported capture isn’t a random stunt.

This board has been set for years. President Trump has been trying to force Washington to stop treating China like a customer and start treating it like the rival it is. Liberation Day was the moment that strategy stopped being theoretical.

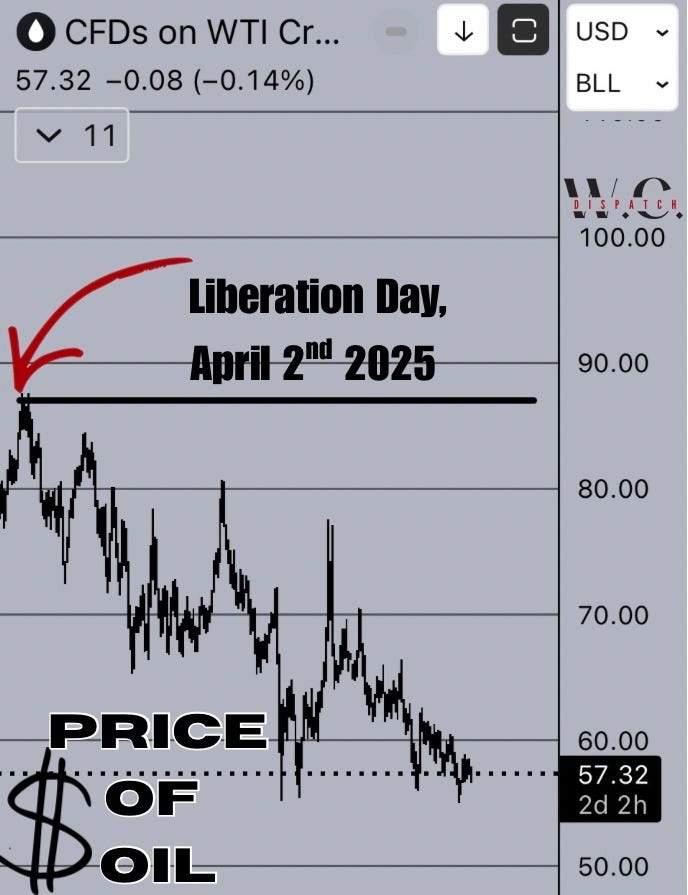

April 2, 2025. Liberation Day. That’s when Trump rolled out the tariff escalation the press screamed about, but buried the lead on. This was not a global trade tantrum. It was a direct, asymmetric hit on China’s export machine. Supply chains froze. Forward orders stalled. Shipping expectations reset overnight. You didn’t need a press conference to see it—you could see it in how quickly global trade assumptions shifted. Demand projections moved. Risk was repriced. China felt it immediately, because China lives and dies on throughput.

That’s the first move. And once global demand expectations crack, energy always follows.

Now pull up the crude chart.

WTI crude, measured by monthly averages, slides from roughly $68 in March 2025 to about $63.5 in April, then grinds lower toward the $60 zone through late 2025. Markets behave when growth assumptions are downgraded. Markets don’t care about cable news narratives. They price factories slowing, ships idling, and marginal demand disappearing.

Oil drifting toward $60 does two things at once. It gives American consumers breathing room at the pump. And it tightens the vise on petro-states whose power depends on energy margins, Russia first among them.

To be precise, this isn’t a claim that the United States “controls” oil prices. Oil is global. OPEC+, inventories, and growth cycles matter. The point is simpler: when oil is weak, the U.S. is positioned to exploit that weakness strategically—by tightening compliance, choking illicit shipping, and raising the risk premium on discounted barrels that keep hostile regimes afloat.

This is where the establishment press starts playing dumb. “Why would cheap oil hurt Russia?” Because Russia’s war machine is financed by energy revenue. Moscow’s budget assumptions are sensitive to price and discount levels, and when margins compress, stress follows. You don’t need a single magic number that “ends the war.” Pressure works through accumulation: lower benchmarks plus wider discounts plus sanctions enforcement equals narrower room to maneuver for a state already burning cash.

But Russia is not the main event. China is.

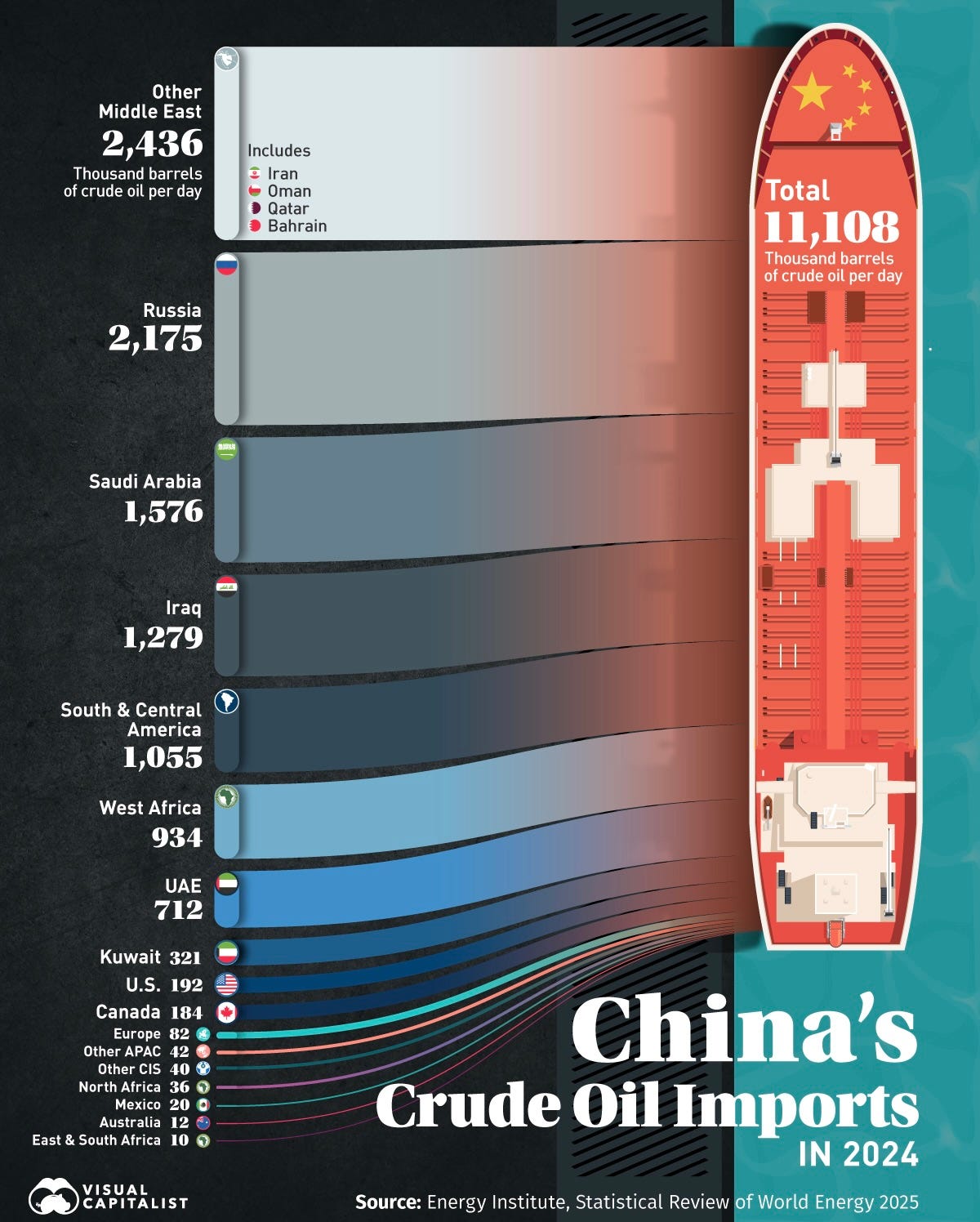

China imports the majority of its crude.

That is the core vulnerability Beijing cannot change quickly:

In 2024, China imported roughly 11.1 million barrels of oil per day, with Russia as the top customs-reported supplier at about 2.2 million barrels per day, ahead of Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. That’s not an academic statistic. That is dependency. A supply chain that lives on ships, insurance, settlement systems, and political relationships.

And then there is the part they really don’t want you focusing on: the sanctioned-origin slice of China’s oil diet. Testimony associated with the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission estimated that sanctioned crude may account for more than one-fifth of China’s oil imports—roughly 1.4 million barrels per day tied to Iran-origin flows, about 268,000 barrels per day from Venezuela, and large volumes of Russian oil moved on sanctioned tankers.

You can argue over decimals if you want. The order of magnitude is the point. A significant portion of China’s energy supply is not clean, normal commerce. It depends on gray networks, relabeling, ship-to-ship transfers, and the willingness of the United States and its allies to look the other way.

So ask yourself: if you wanted to pressure China without firing a shot, what would you do? You wouldn’t blockade the country. You’d make that gray network more expensive, more brittle, and less reliable, while keeping global supply adequate enough that your own economy isn’t punished in the process. That’s how serious power competes, through constraints, not speeches.

The Oil Weapon

Now bring Maduro back into frame. His removal is being treated as a dramatic one-off. Geopolitically, it isn’t. Venezuela is oil, oil reserves among the largest in the world, and a country whose output has been throttled for years by decay and mismanagement. It has also been a source of discounted crude flowing quietly into China.

So what does Maduro being taken off the board actually do? It attacks the discount pipeline. It opens a pathway—slow and uneven, but real, for Venezuela’s production and export orientation to be renegotiated. And it signals something else entirely: the United States is willing to contest influence in the Western Hemisphere again, instead of outsourcing it to NGOs and press releases.

No, Venezuela does not instantly become Texas. Reserves are not barrels at the dock. Infrastructure, capital, and time still matter. But geopolitics is about trajectories. If Venezuelan crude shifts away from gray-market discounts into Beijing’s system and toward normalized exports under a Western-aligned framework, that is direct pressure on China’s energy margin.

And don’t miss the second-order effect. As discounted barrels disappear, China is forced to compete for conventional supply at market terms. Even with soft benchmarks, losing discounts is like taking a pay cut—quietly, steadily, and without a press conference.

Now look at Iran.

The country is restless. Protests have spread across multiple cities, the kind that force regimes to divert attention inward and tighten their grip. President Trump has publicly warned that the United States would not stand by if Tehran starts gunning down peaceful demonstrators. That warning follows a bruising period for the regime—U.S. strikes on nuclear facilities, Israeli operations that removed senior figures from Iran’s military and proxy networks, and leadership that looks defensive rather than confident. None of this suggests stability.

For China, that matters. Iranian crude has become one of the pillars of Beijing’s energy intake, moving at a discount and outside normal commercial channels. If that flow stutters—through unrest, disruption, or political realignment—China doesn’t just lose barrels. It loses leverage. Replacing sanctioned oil means paying market prices and absorbing market risk. There is no switch to flip. China’s factories, ports, and power plants still run on oil, and they still depend on someone else’s political stability to keep it flowing.

China’s Countermove

Beijing isn’t naive. When energy and shipping risk tighten, China looks for leverage where it dominates: strategic materials, processing, and export controls.

That’s why the silver chart matters:

Silver does not climb more than 100 percent in a single year by accident. Monthly averages move from roughly $31 in early 2025 to the mid-$70s by year’s end. That kind of move signals stress entering the system. While energy prices are pressed lower and discounted oil flows are threatened, strategic inputs move the opposite direction—tighter, pricier, harder to secure.

Silver sits at the intersection of industry, electrification, and defense-adjacent manufacturing. Its surge tells you supply chains are being contested, not optimized. When oil gets cheaper and critical materials get scarcer at the same time, that’s not coincidence. That’s a cold trade war showing up in prices.

Put the charts together and the pattern becomes obvious. As oil drifts down and silver rockets up, the oil-to-silver ratio collapses. Energy is being made cheap and abundant. Strategic inputs are being made scarce and expensive. If you want a scoreboard for this contest, that’s one of them.

So, where does this leave us?

It leaves us with a thesis the professional class hates because it implies intent, competence, and stakes. Trump’s posture treats China as the central rival and pressures it indirectly through systems that still tilt Western, energy markets, shipping finance, sanctions enforcement, and hemispheric influence. Maduro’s fall fits that pattern because Venezuela isn’t “just Venezuela.” It’s one of the discount valves China has relied on to keep its industrial machine humming. Tighten that valve, and Beijing’s options narrow.

Victory in this kind of contest doesn’t look like a banner on an aircraft carrier. It looks like higher costs for China, tighter margins for Russia, and sanctioned barrels turning from a bargain into a liability. It depends on whether the United States has the nerve to keep pressure consistent when the talking heads start whining about “norms.”

If this strategy is going to work, the path forward is straightforward: maintain U.S. energy resilience, enforce shipping and financial compliance aggressively, build allied redundancy in strategic materials, and stop letting China use the open Western system as a weapon against the West.

I’m locked out of X but wanted you to know that as I read this article it must be one of the most articulate explanation of a complicated narrative I have ever read! You are a phenomenal .

Thanks for posting this. It’s a great summary of a complex situation that the mainstream news rarely covers accurately. Appreciate the clear breakdown!